|

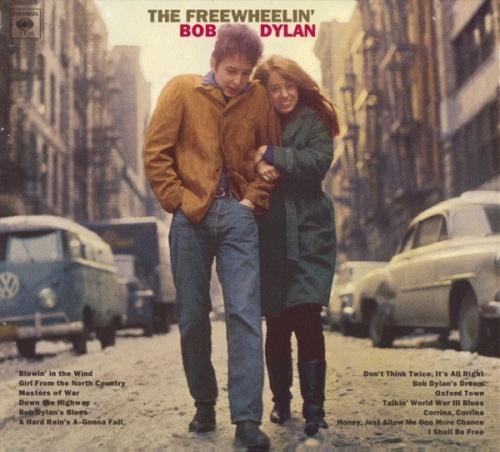

by Abinash Palai On an otherwise uneventful Thursday evening about two weeks ago, the world stopped and wondered why a bard would be rewarded the coveted Nobel Prize for Literature. For some this was a matter of little or no surprise, as they were aware of the genius of Bob Dylan. But for many others it was a prejudice of the same stature as the omissions of Nabokov or Joyce. Within hours of declaration, the internet was bustling with people from either cliques and The Blue Abomination was infested with blogs and posts and open letters. However amidst the frenzy of it all, I put one of his earliest works on and laid back with a glass of wine, because for music aficionados like me, this undoubtedly demanded celebrations, and for alcoholics like me, almost everything did. Of all things that dazzle Dylan’s 50 years of relentless creative produce, I would think that his doggedness stands out the most. Doggedness not in the sense when the New Yorker in 1964 described his voice to be like “a dog with its leg caught up in barbed wire”. Doggedness in the sense that his raw unruly voice, his self-taught guitar chords, and his warbling harmonica, which should have been inadequate, somehow thawed something frozen deep inside of us. When a young Robert Allen Zimmerman from Duluth, Minnesota started on his journey to New York, he had no idea where his adventure would land him. He grew up listening to Woody Guthrie and other folk artists sure, but his thoughts were far from being formed. That teenager defied all odds to go on to become the eternal troubadour of his times and the times to come, and revived as well redefined the entire genre of Folk Rock music. As much as I don’t like clichés, it was a woman who changed and amplified much of Dylan’s early work. Dylan’s first album succeeded his hard fought struggle in Greenwich, New York, during which he played in coffee houses extensively, and could not afford a single apartment. His eponymous album released in 1962 didn’t catch much attention mostly because he covered popular folk songs, and there were enough hillbilly rockers from Tennessee around at that time already. However, his second album, Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, is considered to be crème de la crème of folk rock. Released in 1963, it’s the first instance of Dylan’s powerful poetry in action, which metastasized into a Nobel Prize subsequently. I almost pre-emptively put it on, and sipped on to my cheap red wine that Thursday evening. Bear with me, while I try to unearth some of the stories that made this album as well as Dylan greater than the sum of their parts. It should be right about here the dear readers should be introduced to Suze Rotolo - the girl who’s seen wrapping her hands around a baby faced Dylan, while they walk down a frozen road, on the album cover. Described by media as “Dylan’s groupie” and by Dylan as “the girl who got away”, both the definitions she wrestled to break down her entire life. Apart from being the poster girl of her generation because of the success of the album, she was a jewelry designer and artist. Dylan fell heads over heels for her since their early meetings. In the first volume of his memoirs, Chronicles, Dylan wrote of their first meeting: "Cupid's arrow had whistled past my ears before, but this time it hit me in the heart and the weight of it dragged me overboard." Rotolo was the one who educated Dylan in the ideologies of the left, belonging to the working class Italian communists. Rotolo also introduced him to his lifelong poetic inspiration Arthur Rimbaud. In her book “A Freewheeling Time”, she speaks of the wonderful years she spent marching and rallying with the political activists in Greenwich (for which she had to leave home). In high school she travelled to Cuba, protesting against the Movement Ban, and met Castro and Guevara. If it wasn’t for Suze, we might have had a very ordinary Bob Dylan, faded and forgotten like so many of his other counterparts. “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” was written by Dylan when Rotolo decided to extend her stay in Italy. Set to the magnificent finger picking of session guitarist Bruce Langhorne, the song speaks of heartbreak and unmet expectations. The melody is adapted from Paul Clayton’s 1960 number: ”Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons?”, but is brought to life by the fast paced picking and crude and semi-skilled harmonica warbling. The lyrics of the song are painstakingly painful, and phrases like “Goodbye's too good a word, babe” and “I once loved a woman, a child I am told/I gave her my heart but she wanted my soul” have been witnesses of so many of my heartbreaks and difficult nights. Even now, the wine tastes funny with this song. Maybe I’m a little reminiscent, a little nostalgic of the people that could have been but could not be. Maybe I’m a little drunk. Transcending from one subtle matter to another “Girl From North Country” borrows its lyrical components from “Scarborough Fair” (immortalized by Simon and Garfunkel), and is surprisingly one of the better sung songs. The guitar accompaniment is again delightful. Perfect for remembering an old love, and a poignant walk down the memory lane. “Down the Highway” is a livid blues song full of angst and apprehension towards Rotolo. “My baby took my heart from me/She packed it all up in a suitcase/Lord, she took it away to Italy, Italy!” sighs Dylan. However like most other blues tracks (including the Talking World War III Blues, and Bob Dylan’s Blues) on the album, this one also falls short. However there’s one blues ballad which brings out the wryness and humour of Dylan profusely. “I Shall Be Free” is a rewrite of one of Lead Belly’s popular melody, “We Shall Be Free” originally performed by Dylan’s idol Woody Guthrie. Although the song does not sit well with some of the critics, who have often compared this last track of the album to be “tucked in like shirt tails”, I’d like to believe that this song houses some of the most hilarious lyrics ever. For instance “Well, my telephone rang it would not stop/It's President Kennedy callin' me up/He said, 'My friend, Bob, what do we need to make the country grow'?/I said, 'My friend, John, Brigitte Bardot,/Anita Ekberg/Sophia Loren/Country'll grow'.” Such lyrics set to an upbeat guitar chord, and intermittently interrupted by haphazardly played harmonica, feel spontaneous, genuine and funny. Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan was not just a garland of love songs punctuated by blues-y tracks. It had a bigger agenda which made our troubadour not just a poet, but also a prophet. Dylanesque elements now included social and political commentary to the list of sub-par vocals, stellar lyrics, blues influence, and crude harmonica chords. One of the most celebrated songs of Dylan has to be “Blowin’ in the Wind”, a set of rhetoric questions asked with an ambiguous indication towards the answer. The soothing guitar piece transitions smoothly into a calm and serene harmonica melody, and the song blossoms in its lyrical richness while it tries to denote the futility of war. “A Hard Rains-A Gonna Fall” which is an adapted version of the Scottish folk tune ”Lord Randall” is an apocalyptic prophecy about the end of days. This song would go on to set a benchmark for lyrical and poetic prowess of songwriters. Some critics speculate the Hard Rain in the song is a reference to nuclear fallout which could have resulted in from the Cuban Missile Crisis. Beatnik Allen Ginsberg reportedly cried after listening to the track and announced that he felt as if “the torch had been passed to another generation”. Dylan has this knack for painting pictures with adjectives, and he uses oh-so-many of them in this song. Its heart-wrenching lyrics are an attempt to encapsulate all that’s wrong with the society of the 60s, and lacks nothing if compared to any great poem. Lyrics such as "And I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it/And reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it” made Dylan a much needed amalgamation of an enlightened bard and a mystic prophet whose words must be heeded to. If anyone is of the opinion that Dylan should not be considered a poet, I strongly suspect they haven’t given this song a listenin’. My ultimate favorite song of the album however is the sharp condemnation of warmongers in the form of “Masters of War”. Although the arrangements of the songs are not original and are borrowed from Jean Ritchie’s Nottamun Town, the lyrics are indeed spewed by a war-frustrated Dylan (P.S. : You could see how so many of his songs were not original pieces of music, which strengthens his claim for Nobel for Literature, in my opinion). Masters of War is quite different from all his other anti-war songs as it is anti-pacifist as represented by lyrics such as “And I hope that you die\And your death’ll come soon”. Also the lyrics are more unambiguous and direct as in “But there’s one thing I know/Though I’m younger than you/That even Jesus would never/Forgive what you do.” This is where the Dylan’s defiance distills out. No wonder this became the anthem for the Anti-Vietnam War protests. Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan is a testament to his ever-lasting legacy. It’s the first time the geezer with the hat played without acclaim and in order to convey a message. This album marked the beginning of more than half a century of pure and uncompromised genius, compounded by the courage to call the bullshit. When someone said that pen is mightier than the sword, Dylan laughed and croaked away a couple of lines from the top of his mind, with simple four chords, and people knew strength. The songs of this album were not only commercial blockbusters but also social ones giving voices to many rebellions and movements, and imparting strength to the defeated. Apart from proclaiming that war is not the answer, Dylan also makes sure one understands that love could be. And if it is not, there is always the wine.

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram to be notified whenever we release new articles.

Do you use an RSS reader? Even better!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed