|

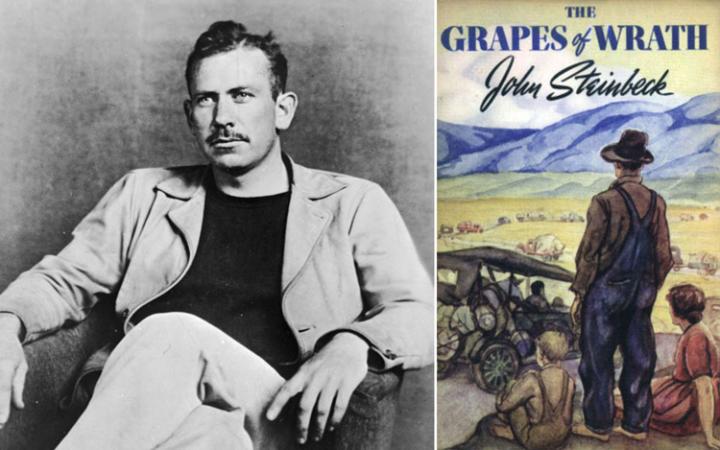

by Srijon Mukherjee “I’ve done my damndest to rip reader’s nerves to rags, I don’t want him satisfied”, quoted the synopsis on the back cover of John Steinbeck’s ‘Grapes Of Wrath.’ I vividly remember sixteen year old me rushing out of the library with a copy of the book in my hand, almost running all the way home. I loved a good challenge and having read recently read George Orwell’s ‘Nineteen Eighty Four’, knew what it was like to have your nerves ripped apart by a mere book. And I loved the feeling. It led to disappointment though, being very different from what I expected, and I dismissed it as a sad, maybe touching (I’d barely read five pages) recap of the Great Depression and how the poverty stricken farmers adjusted. I had no time for the past then, I was too busy reading and speculating about the future, and I forgot about the book, until I picked it up again, from the same library, a week ago. After reading it, I can say, that I’ve finally understood what sixteen year old me assumed wrong: He plays with your nerves and doesn’t leave you satisfied, yes, but that’s not because he tells you about a future we can’t escape, or a uncomfortable present that we’re stuck in, like you may expect from a dystopian novel, but because he narrates a past where society was divided into two parts - those who did not need but wanted and thus oppressed, and the oppressed who needed -something that I was not ready for then. ‘Grapes Of Wrath’, primarily realist and modernist, was published on this day in 1939, and despite being an instant bestseller, it attracted a lot of controversy, being labelled as ‘socialist propaganda’ and accused of being overtly exaggerated. Two decades later, it won Steinbeck the Nobel Prize for Literature. It’s set in the time of the Dust Bowl, a period of severe dust storms, that completely ruined the agriculture of the parts it hit. The banks also start forcing tenants out of their lands, to grow cotton them. This forces many farmers to leave their homes and migrate to California in search of work, and the novel focuses on the Joads, one of such families. The work itself is not too endearing and involves picking fruit and cotton from the well off land owners' produce, but the hungry farmers are ready to take whatever work they can get. Though the novel shifts narrative in the perspective of other characters too, the eldest son, Tom Joad is the main protagonist. His family consists of him and his two grandparents, parents and five siblings. Also traveling with them is the former preacher of their town, Casy, who later proves to be the main perpetrator of Steinbeck’s philosophy. Though optimistic about their chances of making a satisfactory living in California, the farmers are soon to be dismayed: It is made clear early in the novel that there is only work for a limited amount of farmers, a fact that is kept secret from the poor migrants; a ploy to lure large numbers of farmers into the state and use the intense competition among the poverty stricken people to get labor for cheap prices. And thus Steinbeck begins playing with the reader’s nerves by relating to him an entire account of a deluded journey made by strong buoyant farmers, which he can only read and do nothing else. The farmers are considered to be uncivilized barbarians by the city inhabitants, and are referred to as ‘Okies’, since a large number of them come from Oklahoma. They are treated as untouchables. As more and more hungry and desperate men migrate to the city, looking for work and not finding it, a change starts to come over both parties. The capitalist farmers are overwhelmed by the sheer number of deprived men now walking about, realizing that the desperation and growing discontent of the men could soon lead to a revolt (ironic, seeing how they are the cause of the discontent of the farmers), and they start adopting extreme protective measures to prevent them from grouping together, arresting and killing anyone showing signs of antagonism. Meanwhile, the same growing discontent seems to unite the farmers, and they realize that their only chance of survival is if each man lives and sacrifices for the other. They soon start forming self governed communities among themselves, and seem to prosper, albeit facing extreme hostility from threatened city dwellers. What is most disturbing about Steinbeck’s account of the Dust Bowl, is that despite the intense description he provides about the terrible ecological factors during the time, the migrants find their toughest enemy not in nature, but from humans. The reader at first is given extremely detailed descriptions of the process of degradation of the land and the other environmental changes that render the farmers helpless, but however, on further reading the reader realizes that the farmers still could have gotten past these horrible conditions, had they not found such opposition from members of the same species. Aside from the main narrative through the Joad family, Steinbeck also adds intercalary chapters, that provide a universal historical account of the main events that transpired during the time. These chapters employ a number of literary devices, including -but not limited to- repetition and symbolism, and a stream of consciousness narrative to depict the degradation of the land, roadside car dealers cheating farmers desperate for fuel and spare parts, banks seizing land from the farmers, and other happenings on the road, that provide a wider view of the journey and hardships faced by the farmers. At times, the chapters address the reader in second person, as if the reader is one of the deluded farmers in search of work in the city, and proceeds to dismantle and consciously mock the circumstances. This strange personalization and cynical behaviour serves to instill in the reader the same distress faced by the farmers he is reading about, and as we’ve come to expect by now, maybe even take a good shot at said reader’s nerves. Though it makes obvious political points against capitalist greed, the novel is also an extension of Steinbeck's philosophical beliefs and ideas, as observed in the actions of the characters he writes about. Jim Casy, though not part of the Joad family, is one of the most important characters of the book, as he is the main medium for Steinbeck to express his views with regards to the status quo in the book. Ma Joad(Tom’s mother) and Tom Joad also serve as mediums, though unlike Casy, Steinbeck focuses more on their character development than their own quotes and epiphanies to make his point. From the very beginning of the novel, Casy, a former preacher, is seen to be disillusioned with the very aspect of religion and worship that is the custom for everyone in the country. In his time as a preacher, he found himself more susceptible to sinful desires than the others, as a result of being too taken and obsessed with the idea of Jesus and worship of him, the irony of which led to his disillusionment. He then wanders about trying to form his own ideas and starts to form the belief that the human experience is not about the individual himself, but rather the collective experience of all the human souls in existence, as one whole, The novel’s depiction of the gradual convergence of the migrant farmers’ identities into one collective poverty stricken community further strengthens his belief. Jim Casy becomes a Jesus-like figure in the novel preaching and reflecting on his newfound beliefs, and sacrificing himself to protect Tom Joad from the authorities after he hits a deputy sheriff. In jail he preaches his new ideas to his inmates and noticing their reaction, he starts to take action and revolt against the capitalist farmers who sought to disorientate the collective experience that he envisioned and later died a martyr’s death, trying to protect the same. In the early stages of the novel, Ma Joad is seen to be extremely religious, asking Casy to make religious speeches whenever she gets the opportunity, and associating any sort of success they come across in their journey to God. As the novel progresses, she is seen to depend less on God, and instead more on her family and the need to keep them together. This state of mind soon extends from her family to entire mankind, and she realizes that the mankind will always prosper by ‘holdin on’ in spite of whatever may come. Staying together as one and shrugging off whatever problems arise is central to the human survival and existence, and forever will be. The advent of this notion is also predicted very early in the novel. The third chapter of the book deals with a turtle’s efforts to reach a slightly higher embankment from the highway. A car swerves in order to avoid hitting it, while a truck hits it on purpose, and its protective shell ensures that it is not harmed, though knocked off the road. The turtle then slowly climbs back on the road and continues on its journey. The protective shell, and the turtle's efforts to continue on its journey symbolize the tough skin of mankind, and his stubborn instinct of survival. It also alludes to the Joad family's journey, and their resilience on the road. At the very beginning of the novel, we see Tom Joad being released on parole from prison, after killing an inebriated man who had tried to attack him, in his drunkenness. He shows no remorse for his action, saying that he felt that he did what was needed in the moment. Over the course of the novel, Tom Joad is seen to act spontaneously on intuition, being compassionate when he feels that it’s required, but also quick to revolt and attack if angered. He believes that the ends always justify the means and doesn’t seem to care about the ideas and theories that should govern a man’s actions, unlike Jim Casy. Near the end however, after witnessing the plight of the farmers and Casy’s death, he undergoes a change, realizing the importance of the theory that Casy had stumbled upon. He then dedicates his life to spreading these ideas to the entire world to ensure a better life for everyone. While these specific changes in character are only expected from such a gritty and transformative journey, they do more than just help the plot. As mentioned earlier, the spiritual journey and actions of these three characters embody the concepts of the philosophies that Steinbeck sought to disseminate- that of the Oversoul, Humanism, and Pragmatism, respectively. Transcendentalism, or the belief that the individual objects of the world are small versions of the entire world itself, when applied to the concept of the Oversoul, or the unanimate spirit believed to govern the world, leads to the belief that all individual human souls are smaller versions of the the entire soul of the world itself, an idea very similar to what Casy preached. Humanism or the belief in the abilities and values of humans as a whole is also very central to Ma Joad’s optimistic view of mankind and his struggle for existence, while Tom Joad was perhaps the most obvious depiction of Pragmatism. As observed by an article I read, what is interesting about Tom Joad and Jim Casy is that in the later course of the novel, they both exchange their respective philosophical beliefs. In the beginning stages of the novel, Tom Joad, highly pragmatic about everything,is seen to be frustrated by Jim Casy’s constant musings and reflections, and declares that he is a man of actions and prefers to act as things come. Near the end, Jim Casy is seen to be putting his thoughts into action, while Tom absorbs Jim Casy’s beliefs and constantly ponders about an individual’s existence and his relation with other individuals occupying the same land. I felt that the strongest theme of the novel was that of the Oversoul, as it is a constant theme in both the chapters dealing with the Joad’s journey on the road, and the overall account of the farmers’ experiences during the Dust Bowl. In fact, with this theme in mind, one could even find purpose in the interpolating chapters that address the reader and in the author’s wish to rip the nerves of the reader apart: to make the reader one with and suffer through the communal suffering of the farmers, and thus, transcend the belief of the Oversoul beyond the scope of the book, almost pragmatically, in the guise of a humanitarian experience. I'm glad I read the book now and not when I was sixteen.

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram to be notified whenever we release new articles.

Do you use an RSS reader? Even better!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed