|

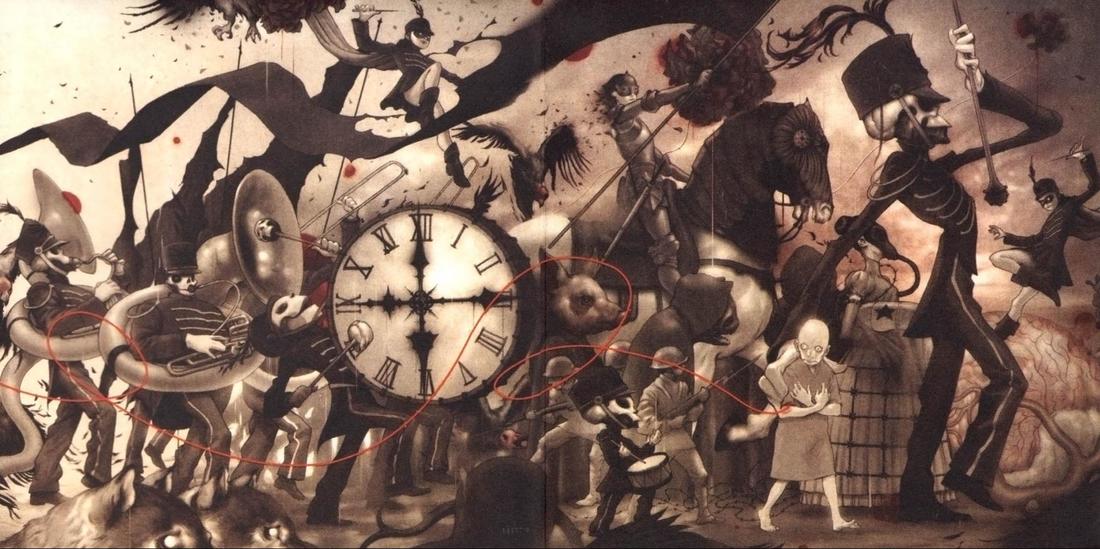

by Shataparni Bhattacharya Punk rock is the voice of the disillusionment era. It was created by a generation of youths who primarily considered themselves to not be artists, but working-class individuals, who faced a set of social and economic problems, including but not limited to mental illnesses. Though largely neglected within discourses of illnesses, the punk rock genre has been a champion for the cause of drawing attention and awareness to various illnesses, usually psychiatric. While it would be wrong to state that it is a voice of authority, it has arguably been the most important cultural phenomenon that incorporated within itself, the many facets of cynicism and defiance that are a part of a disillusioned youth’s attempt to be heard over the cacophony of consumerism – a consumerism that permeates through even into the medical spheres, and thus, the very existence of a physical self, and by extension, the spiritual. The Black Parade was the third album by My Chemical Romance. It is a rock opera, and congruent with the initial stages of the punk movement, the band made an overwhelming use of costumes, make-up, and aesthetics. On the face of it, the album follows the story of a character – referred to as The Patient – and his journey from the cancer recovery process, apparent failure, the last stages of his disease, and death. Death comes for The Patient in the form of his fondest memory – a procession that he had witnessed in the city with his father, as a child – which leads him into the realm of Death. This macabre procession, The Black Parade, which guides him in his journey in death is constituted of various figures such as Mother War, The Soldiers, The Twin Wolves of Hell, and personifications of the emotions of Fear and Regret. Thus, superficially, the album merely tells the tale of a cancer patient, who is led into the afterlife in his death. However, I will attempt to deconstruct this illusion. Let’s first discuss the style of narration and the characters introduced in album and the various contexts within which they are placed, followed by a dissection of the lyrics, in order to analyse the depictions of illness and death, which, as we’ll see, conceal a larger discourse on the themes of apathy, passiveness and eventually, the regaining of agency, that are put forth in the album. The album follows the Everyman style of narration, thus making it akin to a morality play. The Patient takes on the role of Everyman, and the emotions of Fear and Regret, as well as the various characters, though not having an active voice in the album, are reminiscent of the characters of Fellowship, Goods, and Knowledge in Everyman. The album also follows the fairy-tale style of storytelling, especially similar to oral traditions, because there are two distinct voices in the narrative that are heard throughout the course of the album – that of The Patient, and that of The Black Parade. Elements of fairy tales are very evidently placed throughout the album – mirrors, wolves, mothers, as well as the stark illusion of it being a Gothic horror story, akin to the Grimm Brothers rendition of the “children’s” tales. The combination of these two elements – its morality-play-esque nature and its use of fairy tales – lends itself to the theme of growing up. The overarching story, underneath the layers of illusion, narrates the tale of the Everyman character who is shackled by his own apathy and passiveness. During the course of the narrative, the character seems to “die” and is placed within various illusions of the afterlife, including “Hell”. He goes through various stages of anger, fear, and regret at his own apathy while alive. Arguably, unlike the Everyman narrative, the character does not die and eventually decides to take back his own agency. The band (as The Black Parade) seems to be telling the listener (as The Patient) to shake off their apathy. It is addressing the feelings of anger and hopelessness, combined with that of not having agency, which prevail throughout most of an individual’s adolescence and early adulthood, and if not worked upon, remain throughout their life. The Patient’s cancer thus becomes not only a literal physical illness, but a metaphor for the illness of the soul that slowly kills the human spirit, as indeed does cancer kill the body. It is important to note here, that like most fairy tales, the album does preserve the arch of narration, wherein the listener is subconsciously being led on to anticipate a moral conclusion. A contradiction arises, however, which serves as a twist to the standard folk-tale narrative. As has been discussed before, The Black Parade is the entity that leads The Patient on his journey into death, reminiscent of the Pied Piper, leading the children of the town to their watery deaths. However, the trope of The Patient reclaiming his agency is a deviation from this. The Black Parade, by taking him on the journey through death (which is no different from the life unlived – his state prior to the disillusionment), and making him aware and regretful of his earlier apathy, is actively urging him to abandon the way of life which will result in him eventually “dying” and becoming a part of The Black Parade. Therefore, when The Patient finally regains his autonomy, The Black Parade has no more control over him, thus negating its existence and rendering it null and void. However, in doing so, The Patient is, in fact, doing exactly what The Black Parade aims to accomplish. This ambiguity, is further supported by the fact that though the theme of drug abuse is recurrent throughout the album, just as the themes of illness and death; its practicality, however, seems to have been purposefully left to the listener’s discretion. Drugs – both as a form of escape from reality, as well as the drugs being medically administered to the terminally ill cancer patient – are questioned in their actual usefulness, and the present author believes, that the drugs are actually merely a form of placebo, which allows the angry youth to force themselves into a state of blissful apathy that is disjointed from the reality that is far too inhuman for a human to bear (for as most will agree, it is infinitely easier to feel nothing as compared to feeling pain and suffering), and the patient into entering a state where he reconciles himself to the idea of death, initially bitter and resentful of the same, and then simply uncaring. Aside from The Black Parade, which itself is the embodiment of one’s fondest memories, though macabre and grotesque, come to lead them into death, and The Patient, the disillusioned apathetic individual whose soul has long died, a number of other characters are introduced throughout the course of the album. The emotions of Fear and Regret are two of the main characters. They find their voice in songs like “Dead!” which is solely about The Patient being confronted by all he failed to do during his life, and this lack of his Deeds are as though he has never lived – he is “just a ghost”, as is declared in the next song, “This Is How I Disappear.” Regret also appears in “I Don’t Love You” where he is too afraid to speak up, and “Cancer”, where he suffers the agony of knowing that he will never fall in love, marry, or beget children. Fear appears in “Sleep” – his sleep takes him through Hell in the form of nightmares, thus, not only are his fears depicted in this dreamlike illusion of Hell, but they also make him terrified of sleeping (because of the nightmares), and by extension, of death (because death is merely an elongated sleep, and Hell is a never-ending journey through his nightmares). “House of Wolves” is a trajectory from the previous themes of illness, loss and death, where The Patient is led into Hell. The wolves, once again, are a reference to the fairy tale style of the narrative – the Big, Bad Wolf. The Patient is taken through the Hellish journey of the hurt and suffering he himself has caused. The Soldiers and Mother War are brought into the narrative in “Mama”, where The Patient continues to journey through Hell. The lore goes that Mother War had five sons, the Five Soldiers, who, deprived of love from her and considering each other rivals, went to war against one another. Mother War disowns her sons in disappointment. On the eve of the last battle, all five of them realise that they will all die, and write letters to their Mother, informing her of their imminent death. Mother War realises all too late, that her sons are now lost to her. In their death and descent into Hell, however, the sons seem to be hand in hand with each other. The theme of Regret continues throughout this song, where The Patient through the voice of the Soldiers, talks about changing nearly every aspect of his lived life. This song also draws attention to the apparent lack of agency of The Patient (and The Soldiers) – The Soldiers blame Mother War for the turmoil, and The Patient blames his own mother for giving birth to him. Thus, the mother figure is cast into an antagonistic light – where The Patient has given up all agency, and therefore responsibility, for his own actions, and are projecting them onto her. “Teenagers” is a jump back to the present where the entire demographic of the youth who haven’t yet been disillusioned, are being given a voice. They are the ones who are still angry, who still feel, and whom the world has not yet stripped of care. A direct continuation of the trope of characters of the Teenagers introduced in this song, is “Disenchanted” – the disenchantment and disillusionment of those who still had enough agency to be angry, to lose this belief in their own agency. This, then, can be considered to be journey of The Patient himself – from the zealous youth to a jaded adult, yet an adult as devoid of agency as a mere passive child, a child to whom this macabre fairy tale is being narrated by The Black Parade. The album begins with the song “The End”, which, like the once-upon-a-time beginning to fairy tales, is an invocation to action. The album opens in the voice of The Black Parade. The line, “Now come one come all to this tragic affair”, in the classic style of oral traditions invites the listeners to gather around to listen to a tale. The song introduces two concepts, the first, is the use of the word “you”. Here, the listener is actively being made a part of the narrative, and being directly addressed. Second, the use of the words “piggies”, is infantilizing the listener – turning him into a child being told a fairy tale. In this introductory song, The Patient is being made privy to a glimpse of his own funeral – this sets the stage for the revelations that The Black Parade will take him on during the course of the album. The line “When I grow up I want to be nothing at all!”, while at first negative in its connotations, actually attempts to give agency to The Patient – when one is “nothing”, one is devoid of all expectations, and then one is free to become anything. The next three songs are in the voice of The Patient. “Dead!”, serves as a depiction of Regret, through which The Patient’s agency is negated. The Patient’s own life is not within his hands or so he believes. This may also be construed as him receiving the news of his terminal illness. Here, we see a man who is no longer in control of his life – he pleads with his doctors, asking them if it just is not possible for him to live for more than the time they have stipulated for him. Just as a bedridden, terminally ill patient loses all control over his faculties and is left unable to experience things, similarly, a person whose emotions have been drained out of him just as cancer drains the health out of its victims, does not find the emotional resource and is unable to live his life – “Tongue-tied and, oh, so squeamish/ You never fell in love” – simply because he believes that he is not in control of his own experiences. Here, however, the voice of Regret comes into play – once The Patient hears the news of his death, whether physical or spiritual, which is where he truly loses his agency unlike earlier, when he merely believed that he had lost it, he begins to be jolted into a sense of longing for all he has failed to experience. The following song, “This Is How I Disappear”, is quite explicitly, the voice of Regret, through which the conscience of The Patient is confronting him with his deeds that caused suffering to others and with the deeds left unfulfilled. The use of the words “boys and girls” is again reminiscent of the act of story-telling to a group of young children. The fact that he has never really touched anyone positively, and therefore never left a mark worth remembering, makes him a “ghost”, even while alive, and really, it would not make much of a difference if he just “disappeared” (“I'm really not so with you anymore/ I'm just a ghost/ So I can't hurt you anymore”). The next song, “The Sharpest Lives” is a very evident ode to the use of drugs. The entirety of the lyrics is a direct address to the drugs by The Patient. From the point of view of a cancer patient, it simply refers to the medication that he is on, which numbs the pain. However, The Patient who is crippled by his spiritual decay, abuses drugs in order to completely dissolve all agency. He prefers to live in a delusion, detached from reality, in order to do away with the suffering that the world has rained upon him (and convinced him to believe that he is a victim of misfortune and events beyond his control), and his own guilt (at his misdeeds) and regret (at what he has missed out on). The fifth song on the album, is the pivotal turning point. “Welcome to The Black Parade”, is the moment of The Patient’s death, physical and spiritual. There is a dual narrative here – the first verse of the song is in The Patient’s voice, and the rest of it in the voice of The Black Parade, with a single verse towards the end, once again in the voice of The Patient. It begins with The Patient passing on to the realm of death, surrounded by his fondest memory – watching a marching band with his father. While he is merely recounting the event, there is, of course, an undertone of regret at not having fulfilled what his father had asked him to (“Would you be a saviour of the broken, the beaten, and the damned?”). The subsequent verses are the anthem of The Black Parade who carry off The Patient with themselves, while singing this anthem. Thus, it is at this point that The Patient begins his journey into the illusion of death and oblivion that The Black Parade wish to show him and warn him of. The anthem talks about how despite one’s death, his memory continues to exist in the realm of the living, solely through the deeds he has done while alive (“And when you're gone, we want you all to know/ We'll carry on, We'll carry on/ And though you're dead and gone believe me, your memory will carry on/ We'll carry on”). In the last verse, the Patient once again appears, and here too he is an unwilling passive subject to all that is happening around him (“Just a boy, who had to sing this song/ I'm just a man, I'm not a hero/ I don't care”). However he does begin to develop a resolve, a side of him which the listener had not yet seen (“Do or die…who we are”). Thus, despite his acknowledgement of the pain and suffering he has been subject to, he grows defiant and accepts it. The Patient meets various characters, most notably Mother War in her gas mask, and after the journey with The Black Parade, he is suddenly left deserted, as the marching band suddenly disappears with the last beat of the drum. He is left standing in a no-man’s land – his psyche, where he must make the decision of whether he wishes to turn his life around, or continue the same way, which will inevitably result in him finally becoming a member of the macabre parade. The following four songs, I believe, are a depiction of the visions shown to The Patient by The Black Parade as he marched with them. In “I Don’t Love You”, The Patient addresses someone whom he possibly loved and who loved him back at some point. His illness, however, caused them to turn away from him, either because of the trauma and stress of being a support system and caregiver for a terminally ill patient, or similarly, because the sickness of The Patient’s psyche and his pathological outlook towards life caused them to grow weary and decide to leave. It is important to note the tone of resignation, here. While the Patient clearly wishes that his love stayed on, he makes no attempt to convince them to change their mind. He passively allows them to break his heart. The next song, “House of Wolves”, is The Patient being shown a glimpse of Hell – the Hell he has created in the space within which he exists in the realm of the living. Here, the Patient takes on the persona of the “Big, Bad Wolf”. He has created various images of himself, which he projects to the various people he interacts with – “an angel”, “a bad man”. However, while keeping up these images, he seems to have lost his true identity even to himself. The heavy use of Christian imagery plays with the dichotomy between the “innocent” and the “sinner”. While the Patient has sinned, he cannot be called a sinner, because, just like a child, when he committed those acts, he acted out of innocence. Thus, he is the Big, Bad Wolf, but it is also a case of scapegoating. His actions were not his alone. While, he takes responsibility for his actions in one of the first instances of trying to reclaim agency, it is important to keep in mind the innocent nature of his supposed sins. The eighth song, “Cancer”, in my opinion, is the most haunting of all the tracks in the album. Here, The Patient is being shown what he has truly become. The cancer has left him “awful just to see”, “soggy from the chemo”, bald, and alone with his “agony”, “counting down the days to go”. He recognises this, and also addresses the fact that the sickness of his apathy is such that “it just ain't living”, without experiencing any of the things that his apathy and disregard for his own agency, had prevented him from doing. Thus, there is an element of introspection here, that is very important to the journey of his character. In “Mama”, The Patient enters Hell, where he is shown the result of his refusal to take responsibility and accept his own agency. Through the voice of the Five Soldiers who blame Mother War for all the evil that has befallen them, he is shown his own actions. Thus, while he is still reluctant to let go of his own apathy and continues to rage towards the world for his misfortunes, he does begin to accept the role he had to play (“You should've raised a baby girl, I should've been a better son”). The next song, “Sleep”, takes place in the shadow land of The Patient’s psyche, where he had been left by the marching band, at the end of “Welcome to the Black Parade”. This is the point at which he must make the decision as to next course of action. This is yet another pivotal song, where we see him reclaim his own agency. Throughout the song he describes the horrors he had seen in this illusion – the dreamlike state of sleep (an impermanent death) within which the visions had been created. While, the decision was now his to take, the trauma of what he had witnessed would definitely stay with him. In the first verse, he describes the experience of what he had witnessed in the illusions created by The Black Parade. Here, once again, the fairy tale tradition is invoked. The Patient is the child who has suffered at the hands of the awful visions he had seen, and now that he had been shown all that could have been shown to him, The Black Parade had done all it could do. The Black Parade could now “walk away a saviour”, because it is entirely up to The Patient, if he would suffer as “madman” because the visions had now made him fearful of sleeping, or remain apathetic and “polluted, from gutter institutions”. In the next verse, he describes his disgust at his own self for his misdeeds and apathy, and the system within which he had become what he had, and also expresses his refusal to go back to the state that he was in before he met The Black Parade (“Three cheers for tyranny/ Unapologetic apathy/ Cause there ain't no way that I'm coming back again”). While reclaiming his agency, he also talks about his fear of sleeping, because the visions had come in the form of nightmares. Thus, he is not, and never will be, completely cured of this sickness. The next two songs, “Teenagers” and “Disenchanted”, journey into the past and chalk out The Patient’s descent from an angry, expressive adolescent, to the disillusioned adult he had become before The Black Parade led him on the march. The two songs create an imagery similar to the narrative of brainwashing in Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. “Teenagers” talks about the institutionalised procedure of forcing young individuals into a mould, keeping them under close observation, squashing all forms of individuality and creativity, and eventually tearing their “aspirations to shreds”. The Patient was once one such teen, however, the systematic conformity he was supposed to adhere to, succeeded in transforming him into another one of the “cogs in the murder machine”. Once conditioned, he began to fear the very teenagers, like whom he had once been. “Disenchanted” is The Patient reminiscing about the last few glory days when he was in possession of his own mind, so to speak, before he was turned into another “sad song with nothing to say, about a life long wait for a hospital stay”. The last official song of the album is “Famous Last Words”. The most powerful song of the album, it is a conversation between The Patient and The Black Parade. The Patient has been jolted out from his passive state by the visions shown to him by The Black Parade. He has reclaimed his agency and he is ready to take active control of his own life and actions. He realises that the system within which he exists will make it extremely difficult for him to hold on to his individuality and his will to care. However, as he vehemently says – “I am not afraid to keep on living/ I am not afraid to walk this world alone”. His decision to refuse to join The Black Parade, or passively allow them to take him with them, gives him control over his own life (and death). This renders the very existence of The Black Parade void. However, the objective of The Black Parade was to show him the fallacy of his apathy, and force him to make a decision regarding his own life. He has apparently beaten the cancer of his soul, and the album seems to end on a disturbing and intense, yet happy, note. The last and bonus track at the end of the album is called “Blood”. The song is a brief epilogue to the album. The Patient says that he has given the system gallons of “blood”, but it will never be enough. He calls himself “a celebrated man amongst the gurneys” and “the kind of human wreckage that you love”. Despite the rather morbid lyrics, the song is set to a surprisingly catchy beat. This dichotomy compels me to believe that The Patient has descended into insanity. His decision to regain agency was an act of rebellion against a system that benefits from terminally ill cancer patients lying in hospital beds and pumping money into the economy. When the cancer is cured, when the individual takes back control over their own life, it poses a direct threat to the system. Therefore, steps are taken to reintegrate the deviating individual into the institution of conformity. All evidence points to the fact that The Patient, now instead of being admitted in a cancer ward, has graced the four walls of a psychiatric ward, yet within the institution of the same hospital. At this point, it is important to ask oneself that had The Patient decided to stay on in his passive state, since he would after all be making a decision, would this very act of decision-making to remain passive inadvertently give him active control over his life? Would a conscious decision to remain apathetic, itself be an act contrary to apathy, thus allowing him to reclaim his agency? I’d say so. I have interpreted the use of “cancer” in this album as a crippling apathy – a symptom of depressive orders. The nightmares and inability to sleep are also symptoms of the same. The psychogeographical terrains that he traverses while being led by The Black Parade, heavily deal with the ideas of self-loathing, death and loss. This, along with the apathy, are signs of passive suicidal ideation. The Black Parade, I believe, was conjured up inside his sick brain in order to make an attempt to fight his disorder. However, this prolonged nature of the visions, negatively affected his psyche in the long run. The apathy, as dangerous as it was, created a buffer between the active thoughts of self-harm or suicide. With this buffer being taken down, The Patient was in a space of complete autonomy – therefore a decision to return to the apathy (put up the buffer) would be just as valid as an active and conscious decision, granting him his agency – even if the result of this was indeed to resort to self-harm or attempts at suicide, which I believe is the case, taking into account the last track of the album.

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram to be notified whenever we release new articles.

Do you use an RSS reader? Even better!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed