|

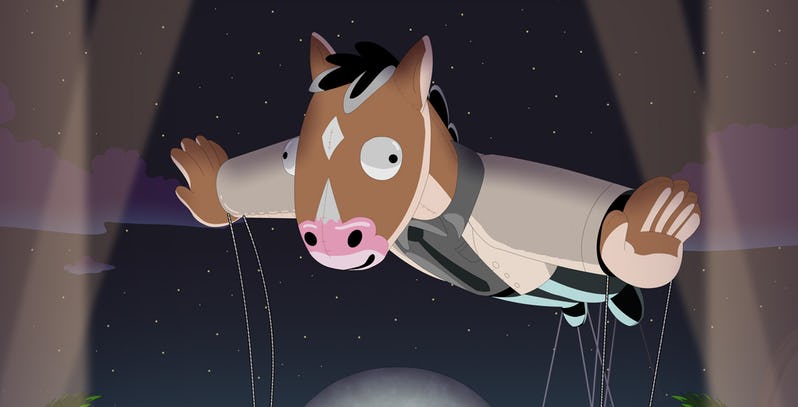

by Luv Mehta So BoJack Horseman just came back for a fifth season this past weekend. Predictably, it's excellent in all the best ways, of course - but in the end, I wasn’t very sure about what I thought of it. After every season of this show I’ve watched before, the first thing that’s always come to my mind has been, “This is the best season of BoJack Horseman yet”. That thought did not come to me this time. There were a lot of criticisms I had, first and foremost being this - how many times are we supposed to see BoJack’s character hit rock bottom? How many times are we going to see another attempt at becoming better being so completely botched? How many times do we have to see him hurt other people? So I rewatched the whole season again. I’ll have to recap some parts of the season, but before all that - there are a lot of plotlines related to other characters in the series that are extremely interesting and worth an entire article on their own. I won’t be able to do justice to them, however, so this article will solely be focusing on BoJack’s plotline. This article is extremely spoiler heavy, so if you haven’t seen the most recent season, now would be a good time to close this tab. Still here? Let’s go.

Season Five shows a fictional TV series, Philbert, about a flawed anti-hero, being filmed over the course of the season. The show is poorly written, exploitative and full of stereotypes, and BoJack is uncomfortable playing this character because it reminds him of himself. Philbert is a man who has suffered great trauma and spends his time hurting other people and pitying himself, and BoJack sees great parallels to that - and after all this time spent trying to be a better person, bit by bit, he doesn't want to see himself be that person again. The show must go on, though, and BoJack tries his best to adjust. When the showrunners hiring a known assaulter backfires, and BoJack’s posturing of himself as a feminist backfires as well, he finally wises up and decides Diane’s voice is needed for the show to be honest. He wants her input to shape the character, and it works - despite great antagonism towards BoJack once she gets to know he almost took advantage of a teenager, and despite her inputs either not being given much importance or being stolen by the showrunner wholesale, she makes it work. BoJack has a stunt go awry and has to deal with his new opioid addiction, but he makes it work. And production on Philbert finally wraps up, and we see the premiere of the show. Early reviews are rapturous, and critics appreciate that the protagonist isn't a simple grizzled anti-hero with some ghosts haunting him, but “a scabbed-over wound of a person" who becomes all the more fascinating as a result. Before Philbert's premiere to the audience, BoJack takes the stage and talks about how the show depicts a man so broken, so flawed, that we can look at him and then look back at ourselves and feel better. All these flaws we see humanizes the characters onscreen, and that, in turn, humanizes ourselves in our own eyes. It’s here that the whole storyline becomes more than just a storyline - but before that, let’s take a step back. There’s this episode in the middle, Free Churro. It’s not connected to the overall plot of the season - in fact, you don’t even need to know much about the rest of the show to be able to watch it. It’s a self contained episode-long monologue on how BoJack’s been affected by his parents, and how he’s always turned to TV to learn how to be better. But, even though he’s internalized a lot for the lessons he’s been taught, he’s also slowly become aware of how this method of learning has been inadequate for him. Becoming better isn’t something you accomplish within the confines of a single season’s worth of time, as he states - it’s hard, it’s something you have to work at all the time. And things don’t become better just because you’re getting better - life is hard, and it never gets easier for you. All you’re doing is learning how to be a bit better at it. And in the process, learning how to make life a little easier for someone else. Because wallowing in our pessimism and nihilism and hatred of the world’s uncaring nature makes us, knowingly or unknowingly, perpetuate these horrors of life. We accept the world as being evil, and we don’t do enough to make sure it doesn’t hurt as bad for the other people in our lives. When BoJack Horseman’s first season came out, critics were initially sceptical of the show. This changed quickly once the second half of the season showed its characters to be far deeper than they seemed to appear at first glance, but it also did something wholly unexpected - starting with The Telescope, episode eight, BoJack Horseman started becoming explicitly critical of BoJack the character himself. The damage he was wreaking upon his friends, new and old, was finally being shown in a negative light, and his arrogance and ego were finally catching up to him, culminating in a brilliant penultimate episode (Downer Ending) where we were guided through his psyche, his trauma and his guilt, the facade being pulled back to reveal a deeply broken man who didn't know what he could do to be better. I will always maintain that this episode is brilliant, a complete masterpiece of narrative and structure and character development. But I also have to acknowledge this - in the process of this storytelling, it ended up humanizing its toxic protagonist and making his behaviour much more relatable to us, the viewers. Our empathy for the character deepened, and I’m not sure this was for the better. Coming back to the recap now, Diane hears BoJack on stage and she suddenly realizes what she’s done - in the process of deepening Philbert as a character and showing how broken he is, she’s also inadvertently given the people watching the show someone to make them justify their own shitty behaviour. Philbert is a failure haunted by the ghosts of his misdeeds and crimes, and he ends up hurting other people as a result, and this, sadly, makes him more relatable to people who are guilty of all the bad things they‘ve done in their lives. And this empathy has ended up glorifying the character they’re watching, giving them an excuse to continue their behaviour, because if someone they watch onscreen is so well-written and human and relatable, while still being as flawed as them, they don’t have to feel bad about themselves. It’s okay to be a bad person, because we’re basically Philbert. And Philbert makes us feel okay to be bad. There’s a musical number in the middle of the penultimate episode of the season, The Showstopper. I wasn't sure what I thought of it at first - it’s a fun musical number right in the middle of one of the darkest episodes of BoJack Horseman, where BoJack is on a Perfect Blue-esque journey towards mental ruin. On a rewatch, it all clicked - the musical number is the whole show, all wrapped up in one neat two minute number, and it all sums up to a personal statement by the entire show that shows one thing above all else - BoJack the show is having an existential crisis. “ You don’t want that. For everything to be fine? How dreadfully boring. ” BoJack Horseman is, for all its uniqueness in the way it delves into the psyche of flawed protagonists, still a show. We’re tuning in because BoJack being a ruinous scabbed over wound of an individual. No matter how much he tries, if he changes, the whole show would change. So he can’t get better, because there’s always more show. “You are a rotten little cog, mon frère. Spun by forces you don’t understand.” All the traumatic memories BoJack sees around him are of the people he’s hurt, the things he’s done that have hurt or even outright killed other people, and they’re all things the showrunners have written specifically for us to watch. “Living is a bitter, nasty slog, mein Herr. Why not sell your sadness as a brand? Paint your face and brush your mane and find some place to cut your pain to portions we can buy at the mall.” His trauma is our entertainment - we’ve tuned in to the show specifically because his suffering and his toxicity has been the selling point of the series all along. “Grief consumes you but you just keep grinning, the ache becomes you and it’s just beginning.” We end up idolizing him because we see his endless spiral of sadness and depression and guilt and it’s hurting us. BoJack can’t become better in one single go, not with neat season finales with simple life-affirmations. There’s always more show, and the next season will bring with it its own pain. It never gets easier, and what can the show do to say it will? If it tells us it will all get better one day, it’s a lie. If it says that life never gets better, it gets trapped in a seasonal monotony of its own making, selling us the sadness we've signed up for. And that’s why all these criticisms of BoJack Horseman the show come so much more easily to me right now - it’s the show itself that has brought these points up. BoJack Horseman’s fifth season is a statement of acknowledgement from the writers, telling us they've messed up. They've created a character in BoJack that is incredibly well written, incredibly flawed and incredibly relatable, but they've also helped a substantial section of the fanbase feel better about being flawed as a result. We see ourselves in BoJack, and we end up justifying all the hurt he’s inflicted upon the people in his life, because that helps justify the whirling spiral of depression and toxic behaviour we often find ourselves in, and the collateral damage we end up causing. So here we are, at the finale. BoJack has hurt someone else now, strangling Gina in a haze of drugs, and he’s not going to be punished or held accountable. Like Vance Waggoner (the serial assaulter shown in the episode BoJack The Feminist), he’s allowed to get away scot-free, and yet another woman lies traumatized in his wake of self-destructive behaviour. Gina won’t tell on BoJack because she doesn't want his assault to be the most notable thing about her life, because at the end of the day, she doesn't want to be remembered as a victim. Because that’s just it, isn't it? You can glorify your self-hatred all you want, but in the end, your self destructive behaviour doesn't hurt just you - it hurts the people closest to you, and they’re left to pick up the pieces and move on with their lives. You may not always know it, but someone’s always got your back. And you can take that sword and run it straight through your heart, but you won’t be the only one who bleeds. “I need help,” BoJack says to himself, finally checking in to rehab, finally making a concerted effort to not be the person he’s always been, for the sake of everyone in his life. Because that’s what getting better entails - it’s hard, and it’s uncertain, and it’s not fun. But in this uncertain, meaningless world, it’s one of the only things that’s right to do. And with all that being said, the question still stands. Should we forgive BoJack Horseman? I don’t know. I’m honestly not sure - maybe it’s because the show’s latest season is an indictment of the whole genre of anti-hero male protagonists. Maybe it’s because there’s no better refutation of the mission statement of the show than its latest season. Or maybe our empathy with flawed protagonists in stories ultimately makes us complicit in their actions. Again - we’re tuning in to a show to watch the journey of a heavily flawed man trying to become better, season after season, and we empathize with him and become defensive as a result. But watching an ongoing show built on this journey also means we’re specifically tuning in with the knowledge that we’re going to see how he makes things worse before they can be better - and this is part of what the appeal to the show has been for so long for us. It’s an inherent contradiction, and it’s one we’re going to have to deal with. So what’s the alternative? Empathy is an important part of being human, and being there for people when they trying and become better really does help them. It helps us to have people who believe in us, encouraging us to be better. Empathy literally makes us better people, whether we’re the ones empathising with others or being empathised with. And yet, our humanity also makes us very, very flawed. Knowing someone is flawed and being there for them despite their problems sounds noble, and being on their side against the world is a lofty ideal for us - right up until we realize that the other side also has the people who they've hurt. And here's the problem - we tend to relate to people like us, and we tend to defend people we relate to, even if they might be in the wrong. What, then, of the people we can't relate to? If they become victims, and the victimisers are the ones we identify with, what then? I don’t know. For all this time spent thinking about this season, I’m ultimately not smart enough to understand what the right answer to this question can possibly be. All I can do, all that’s within my control, is to work towards becoming a better person, for the sake of everyone I know, and learn to give my empathy to the people who are hurt, instead of the ones who hurt others. Our culture places too much importance on flawed men, and it’s time to let anti-heroes die.

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram to be notified whenever we release new articles.

Do you use an RSS reader? Even better!

1 Comment

|

Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed