|

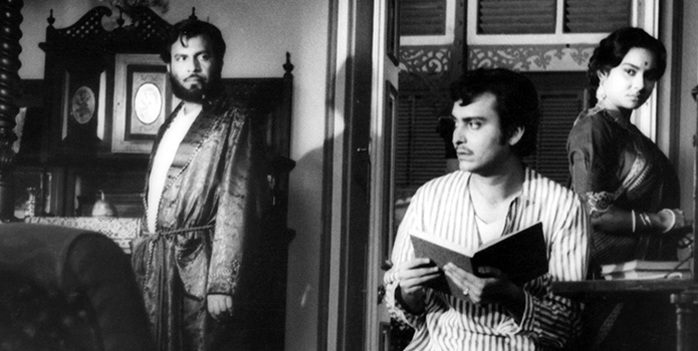

by Vanya Lochan The concept of bhadralok, as opposed to the chottolok, is of great significance in the social history of colonial Bengal. Bhadralok in Bengali stands for the ‘respectable’, the cultured and educated, i.e., the middle and upper classes, whereas in contrast, the chhotolok make for the “small people” or the poorer, lower classes. Bhadramahila are the women of the bhadralok. The concept of bhadralok played an important role in the 19th century cultural renaissance in Bengal and the social reform movements there. What should be further mentioned is the bifurcation that came into the picture in relation to the social and political spheres, and in that sense, there came up a dichotomy of the world into two domains - ghar and bahir, the home and the world. The dichotomy of ghar and bahir did not, however, imply a clear chasm between what was European and ‘material’ and what was ‘inner’, distinctive and spiritually superior. With the emergence of several reformist movements aimed at undoing various oppressive structures of patriarchy such as Sati and efforts at enabling women to attain liberty by means of providing education and equal opportunities, the dynamics created by the confrontation between this ingrained dichotomy and an attempt at renewal of Bengali social structure resulted in the formation of a new kind of patriarchy - something where attempts to construct a ‘new woman’ who was apparently liberated were being made but at the same time, the innate nature of control over the female sexuality could not be overpowered. Ace film-maker Satyajit Ray’s ‘Charulata’ (The Lonely Wife) (1964) can also be understood in a similar light. Charulata is a Bengali film by Satyajit Ray, based on Rabindranath Tagore’s story, Nastanirh (The Broken Nest) taking place in nineteenth-century colonial Bengal, when the Bengali ‘cultural Renaissance’ was at its apogee. Charulata tells the story of Bhupati, a political journalist and publisher, his young wife, Charu, his cousin, Amal, who is almost the same age as Charu and Charu’s brother and brother’s wife, set in the 19th century old-world and feudal Bengali bhadralok which is being ruffled by the winds of liberty and individuality. Deeply inspired by Mill and Bentham’s ideas of freedom and equality, Bhupati, portrayed by Shailen Mukherjee, is insistent upon propagating the same by means of his newspaper ‘The Sentinel’, which runs on his feudal money and is destined to be in dire straits. Bhupati’s enterprise keeps him busy all day, leaving his young, childless (conveniently, though) ‘good wife’ Charu to herself. In spite of being neglected, she is amiable and fills up her time reading literature and looking at the outside world from her sequestered ghar through her opera glasses. It is also interesting to note how Ray portrays the ‘home’ in a Bhadralok vis-à-vis the spirit of patriarchy that binds it. The bhadramahila is provided with the Western equipment- opera glasses and literacy to ‘look at’ the outside world while definitely staying within her part of the world, her ‘ghar’. This rather terse representation of Charu’s relationship with Bhupati is contrasted against the mellifluous introduction of Bhupati’s cousin, Amal, who is also a writer, and his interaction with Charu. Both seem to find a common point on literature as they discuss ‘Bankim babu’s’ (Bankimchandra Chattopadhyaya) Anandamatha and music as Amal sings Tagore’s ‘Ami Chini Go Chini Tomare, O go Bideshini’ to Charu. A stir hits Charu’s otherwise empty but intrinsically calm life with the coming in of Amal, Charu’s brother and the brother’s wife, Mandakini or ‘Manda’. Amal inspires Charu to write and Charu gradually attains the self-imposed right to be the first one to read all of Amal’s work and openly displays feelings of envy when Manda seems to be taking over this right. Slowly, and almost unknowingly, a sexual love develops between the two. By means of these characters, the story discusses social implications trudging alongside personal lives and relationships. The pattern of relationships within the traditional joint family and the complex confrontation is depicted very craftily by Ray, by means of the spatial variation among Charu, Bhupati and Amal, and the various rivals to the attention of Bhupati and Charu - the newspaper for Charu and Amal for Bhupati. The concept of ‘boundary’ and ‘decorum’, which are the pillars of the home-world dichotomy, is very well played with in the parts wherein, when on recognising the nature of Charu’s love for himself, Amal consents to marriage and goes abroad, thus staying within the decorum, but in close contrast to this, when breaking violently from this constraint, Charu collapses on bed on hearing the news of Amal’s marriage, making almost no effort to hide this facet from her husband who, for the first time, comes face to face with this realisation and the intense emotional power of his wife’s grief. Thus, though the entire drama takes place inside the upper-middle class ‘Bhadralok’ and on the surface is about the suppressed romance and characters’ relationships and preoccupations, it is essentially also about a classist and sexist society and a woman’s, a bhadramahila’s desires and dissent in Bengal of the colonial era. And ultimately, the desire and longing of Charu is treated as a fire that engulfs all of the three main characters, but smoulders Charu the most intensely. Unlike Tagore, the maestro, Ray suspends the climax in an animation, leaving the audience to discern the emotional conflagration.

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram to be notified whenever we release new articles.

Do you use an RSS reader? Even better!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed