|

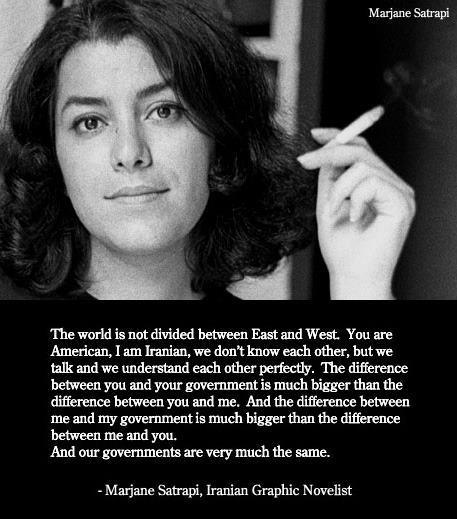

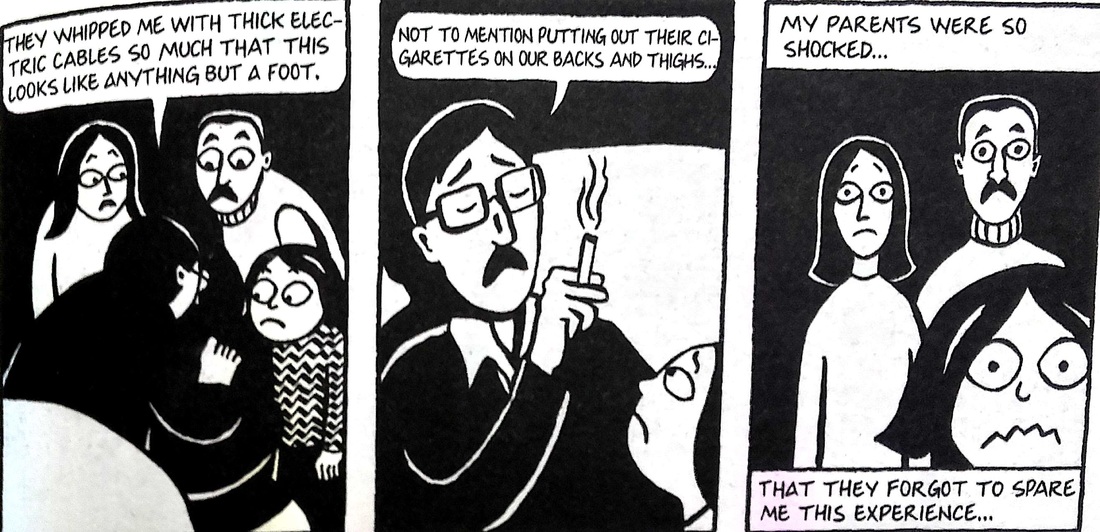

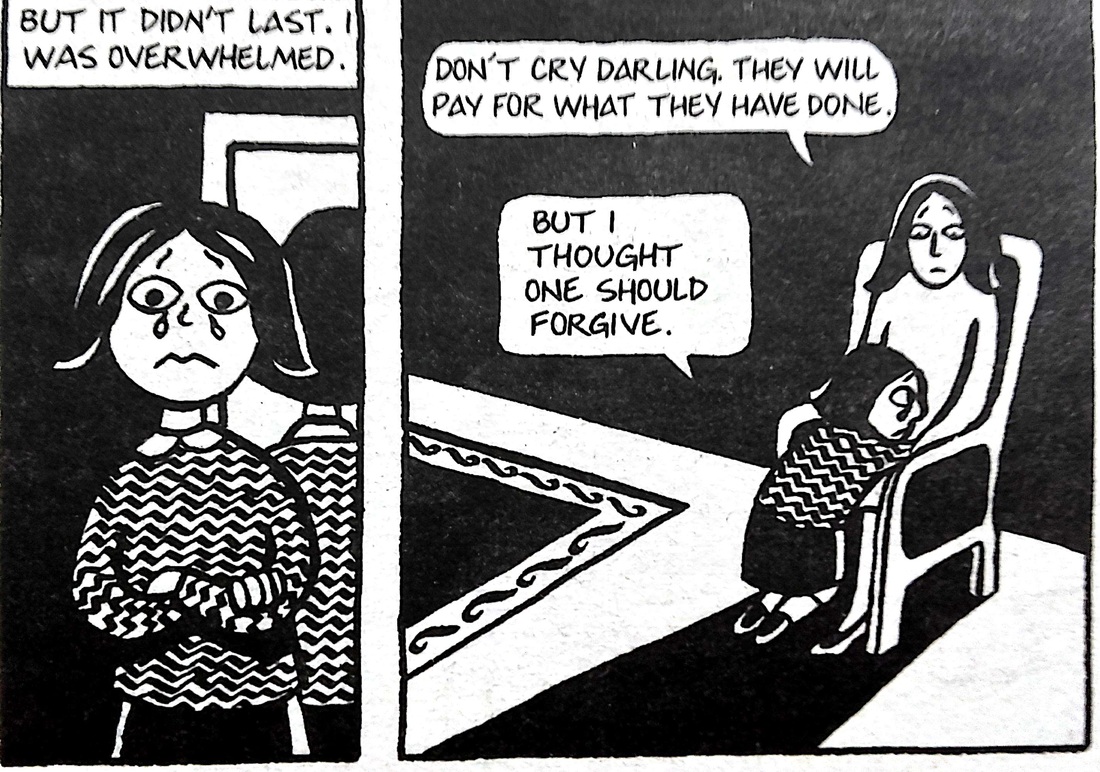

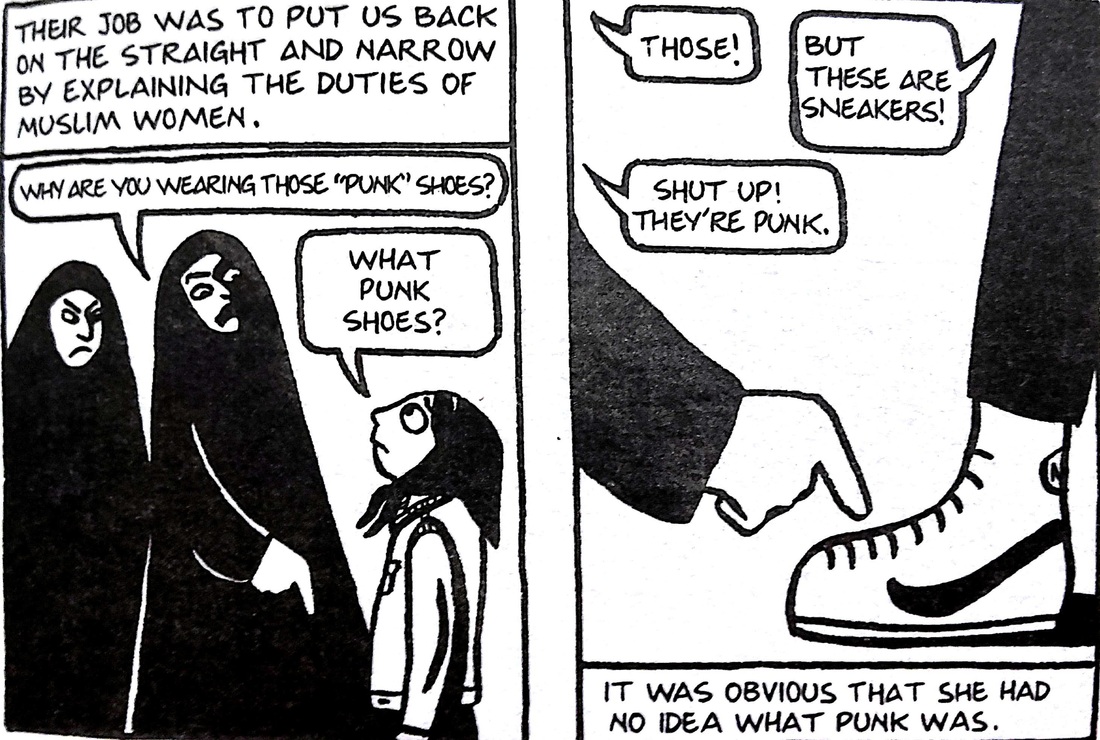

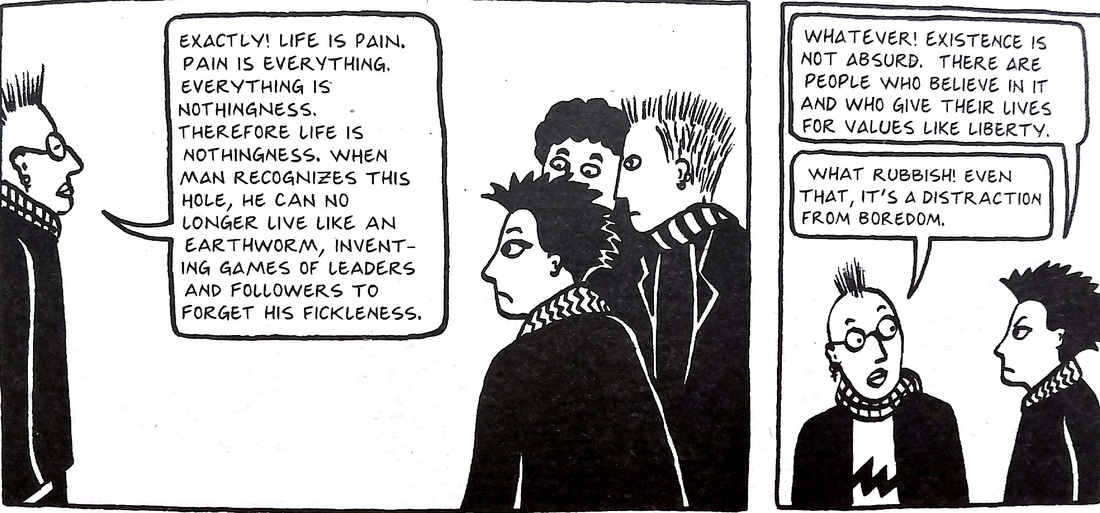

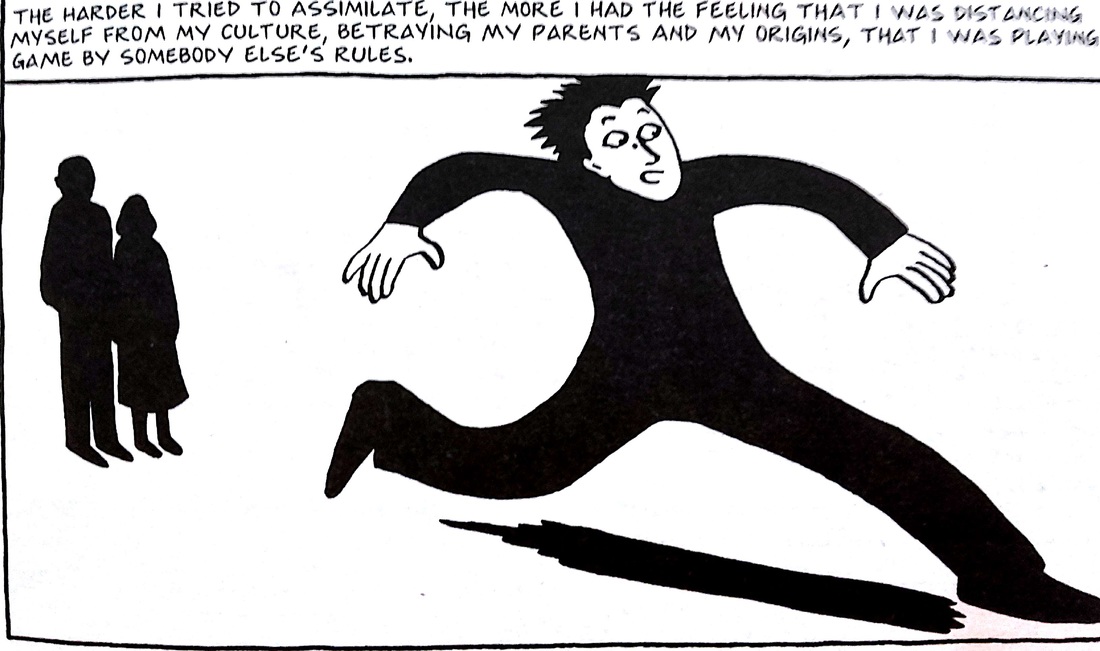

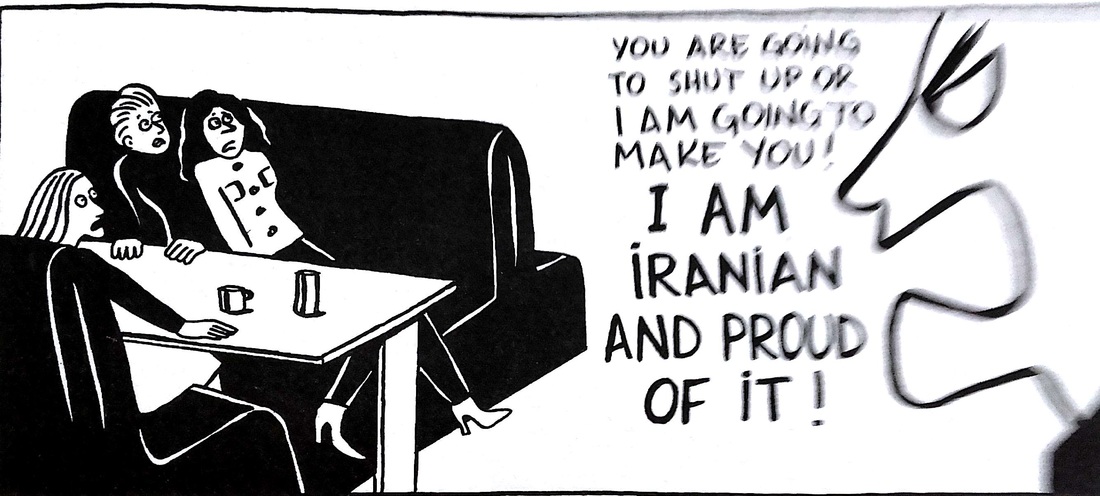

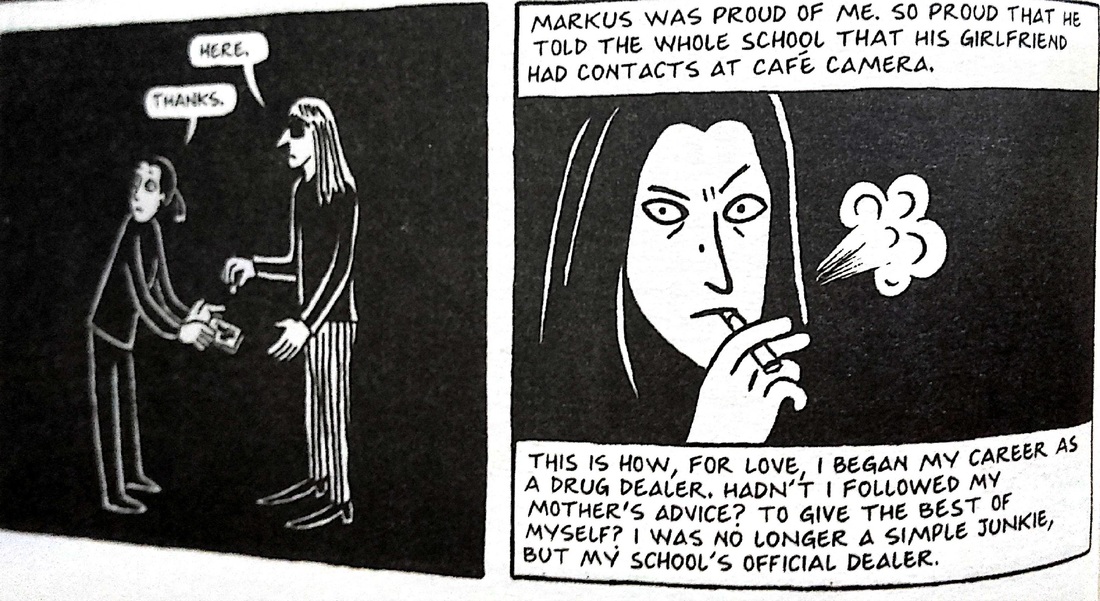

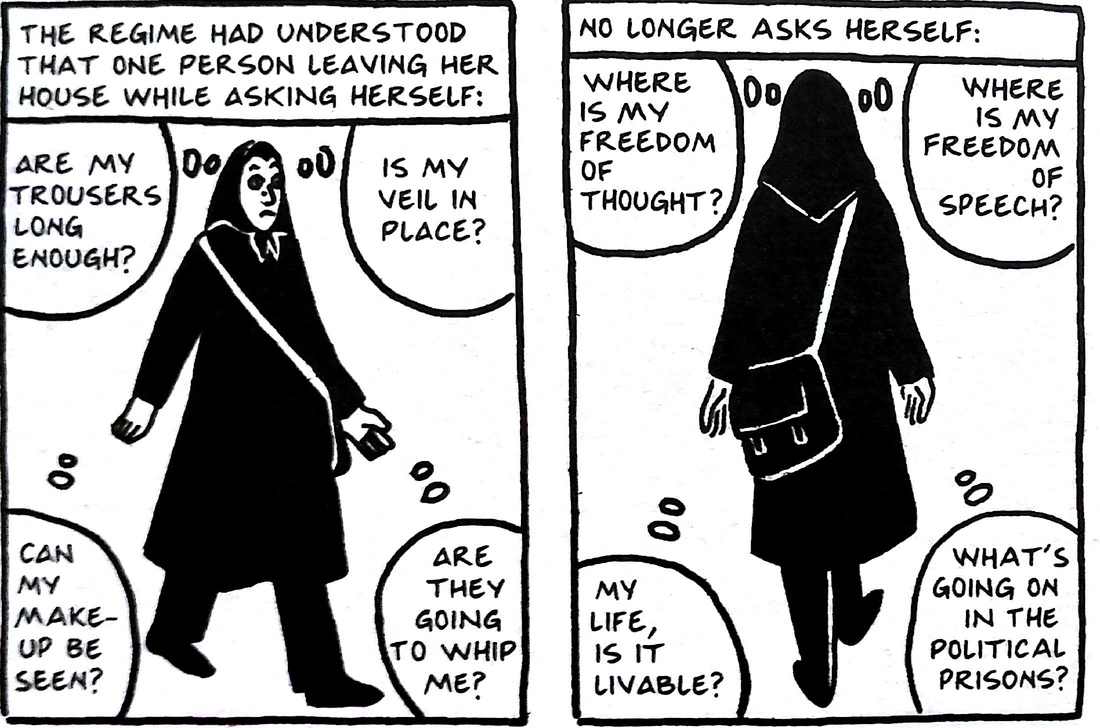

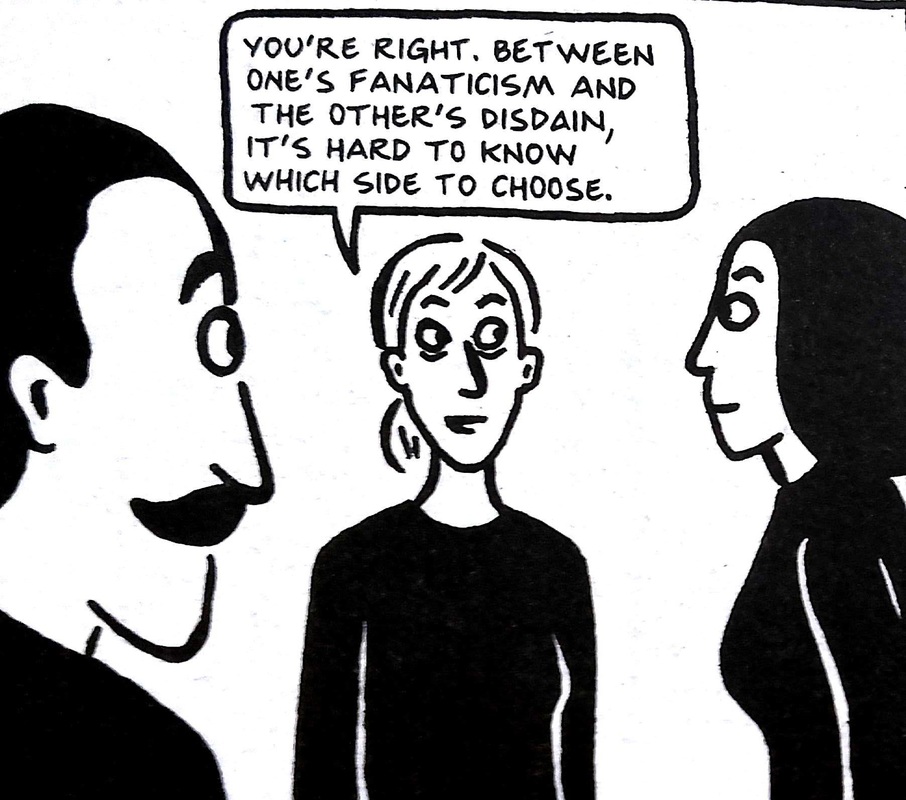

by Radhikaa Sharma I picked up Persepolis on a total whim, knowing (mostly from its name) that its set in Iran, and its author is that lady in the web-wide picture talking about nationalism (you know the one). So imagine my surprise when this book about some of the bloodiest and most devastating times that Iran has been through turns out to be a graphic novel. Don’t get me wrong- though I am, by no means, a comic book guru, I have read sufficiently in the medium to know how efficient it is as a means of reaching its readers and conveying the profoundest of emotions as well as any other form of literature. However, I’ve gotten used to the idea of suffering IRL depicted in words angled to twist your heart just so, and I didn’t see this book doing that. What intrigued me was how an impersonal tragedy of fantastic proportions and real losses and real people (autobiographical, no less) would look in black and white comic panels. I had forgotten something very elementary - the window we choose is the view we get. Satrapi starts, not with the long drawn process of coup and counter-coup that gnawed into the heart of one of the oldest continuing civilizations, but with a story of a ten year old child stuck in the midst of changes too enormous for her to comprehend entirely. “The Veil” is the perfect first chapter, setting the tone for the first book, where a child finds solace in fantasy and fiction, in the familiarity of family, even as the world as she knew it turns on itself. Middle-class safety notwithstanding, the picture she paints is of a country that is struggling to keep up appearances of normalcy even as unrest and oppression pervaded modest dining rooms every day. From a literal God complex to learning about social class to finding and losing a role model warmer and more real than the Almighty, the girl you meet in the first chapter stumbles her way through a troubled Tehran, even as Kim Wilde and Iron Maiden provide her what little comfort a child in a torn country can have. Book 1 is childhood, with all the security of home and hearth against the bleak background of people regularly going missing and bombings sending families running to cellars. Satrapi grows up in a world that splits her identity in two, making it difficult for her to understand where the simple lines drawn for Right and Wrong had gotten blurred. And that’s when it struck me - war isn’t just a tragedy of the masses. It is a deep, personal loss, where families pictures are always incomplete, where nationalism becomes a curse to live with, where your moral sensibilities are challenged and put to bitter test on a near-daily basis. When the powers that be change how the world looks at you, making your country the face of fundamentalism, fanaticism and terrorism, how do you react? How do you scream to the UniverseInGeneral, proclaiming, Not-All-Iranians? If you are fourteen, you rebel. You lash out against the lies you’re fed. You try to stand in the face of what you see is wrong - and you end up scaring the shit out of your parents (sound familiar, eh?). But when you do this in a country where dissent is rewarded with death - or worse - you may end up getting sent off to Vienna, just so you can be yourself in a safer world, as Satrapi was to discover. What makes Persepolis refreshingly different from any other account of life in Iran that I’ve read is that it neither belittles the magnitude of tragedy, nor revels in the pain of a life skirted by privation. Satrapi makes the story so goddarn relatable, that the fierce Irani pride and the daily struggle for life in Tehran seem inherent to the story, just as contraband denim and cassette tapes are. The second part of the book, for the larger part, tells of Satrapi’s life in Austria, exiled for safety and a “real” education at fourteen, countries away from everyone she’s known. Naturally, the stories get darker and grittier as Satrapi grows older and explores the world around her, but the narrative never loses its undercurrent of gentle self-deprecating humour. Even as she discovers Sartre and Beauvoir and found a bunch of hipster friends to educate her, she realises how hard it is to try and hide her identity, and how much harder it is to accept it. Though she fits into her new life near-seamlessly, the memory of her family back home steeped her in guilt that she couldn’t really surface from. Book 2 Marjane is a little bit of all of us - she reads Bakunin to look cool, she pretends to toke when she doesn’t want to, she chops off her hair, she ignores news of bombings back home (okay, maybe not that last part so much). She falls into bed and falls in love and breaks her heart and returns to the wibbly-wobbly relative safe-zone that home is, and starts over again, putting behind “the shame of having become a mediocre nihilist”. The best thing about Satrapi is that, unlike several, several memoirs, she is brutally honest - and that is a very difficult thing to do. Sometimes, it means losing out an opportunity to shock/awe/gratify your readers, and sometimes, it means accepting shades of yourself you’d rather not look at - and she does both these things unflinchingly, repeatedly, and with such pizzazz, one realises that her truth is richer than any exaggeration or romanticization could be. The last quarter of the book, based entirely in Tehran, is no more the voice of a child - it is a woman, unsteady and vulnerable, but slowly building an image of herself in a regime that actively forbade it. From depressed to suicidal to manically made-over, she finds a tenuous foothold in a society that looked at her as an outsider as much as Vienna did. She restarts the cycle of education and love and fighting-the-Man, with a little more empathy and a lot less nihilism. By the last chapter, I realise that the story doesn’t seem to be picking up any loose threads and tying them neatly together. As is usual, I turned to the last page and start seeking closure, but the backward read proved to be unsatisfactory- the book ended as abruptly and simply as it began (no epilogues, either!). But one Google search and a half dozen articles later, I realise that Marjane Satrapi’s story is far from over. It continues in her blog, where she remains as delightfully candid as she was in her books. It goes on in her defending the rights of people wronged by misrepresentation and governments they didn’t choose. It thrives in her choice to call “graphic novels” comic books, and to smoke if that’s what pleases her. Reading about Iran in Satrapi’s tongue made one thing clear: there’s so many stories inside every great one.

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram to be notified whenever we release new articles.

Do you use an RSS reader? Even better!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed